By Carl Wilkerson and Pattie Thomas

Our special thanks to Casey for letting us do a guest blog here at Adventures of a Part-Time Wheeler. We blog regularly as a couple on Psychology Today about disability and caregiving: CWD (Couples with Disabilities)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We are embarking on a special journey this summer. We have decided to make a documentary and we are seeking help from other people to make this happen. Asking for help of this kind is a delicate task, balancing the determined with the annoying.

Big journeys come with risks. One of the risks of fundraising is the loss of friends who are offended by the request. In our society, admitting that you need help and directly asking for help can be regarded as an indication of weakness, or at the very least, tacky. We decided that this risk was worth taking because the project is important. That's how risk goes. You assess the possibilities. You ask, what is worse, the risk or not doing the project? When the answer is "the project," you take the risk.

So we have entered this with the knowledge that people will reject us and we are okay with that. Perhaps they don't have the money. Perhaps they don't believe we are the good investment to do the project. Perhaps they see the importance of this but have other priorities at the moment. Perhaps a reason that we cannot anticipate will stand in the way. That is why this is a journey and not a forgone conclusion.

But if the reason for not supporting this project is because "I'm not disabled, so why should I care?" We to offer the following for consideration.

Las Vegas stands as a case study of both the beauty and the limits of law when addressing the questions of inclusion. The Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) and its revisions, remains one of the most comprehensive and progressive pieces of legislation passed anywhere. Yet, in a city where most of the business district has been built or refurbished since 1990, barriers to accessibility for persons using mobility assistive devices and persons who experience ambulatory difficulties remain. The question is: Why?

The answer is that more than laws are needed. People who design things need to care about a broad spectrum of users. People who finance the design of things need to understand that broad spectrum and be motivated to appeal to them. Unless that understanding exists, the barriers to inclusion happen long before a ramp is put at a dead-end door or a hallway is built too small. The barrier is stigmatization and the lack of social empathy that accompanies it.

There is an answer to this, however:

"Universal Design is the process of creating products (devices, environments, systems, and processes) which are usable by people with the widest possible range of abilities, opera ting within the widest possible range of situations (environments, conditions, and circumstances)." (Universal Design: What It Is and What It Isn't)Universal Design is at the heart of this project and it is something we believe EVERYONE should know about and think about.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here are our top 7 reasons why you should care:

7. Everyone experiences barriers in their daily lives, even if temporarily.

When you are carrying items in from a grocery store and can't get the door opened because of the round knob or when you are pushing your kid or your friend's kid in a stroller in the mall and you can't find the elevator to get to another floor, you are experiencing a barrier. Life's circumstances create barriers. Yes for those of us who deal with pain and disabling conditions, these happen more often, but we really are on a continuum with everyone, not a separate class. Universal Design will not pick and choose which class of people to help. If a door handle is designed as a level instead of a knob, it makes life just as easy for the person carrying groceries as the person who has arthritis.

This phenomenon was seen in so-called handicapped bathrooms that now also serve families with children. The design of a larger space was intended for room for wheelchairs and scooters, but it accommodated strollers. Now many places of business advertise it as such.

6. Almost everyone will know someone who lives with a disability at some point in their lives.

The social world exists even when things are modeled as individual. Disability often is discussed in individualistic terms, but the truth is that barriers impact the friends and family who are traveling with a person living with disabilities as well as the individual. An inclusive world will make it easier to bring Grandma along to the store or the vacation. Need to enter an office building with your coworker who is a PWD, you won't have to separate from them while they take the more accessible route if you live in a universally designed world. Wouldn't it be nice to live in a world where people can go about the business of living and not have to notice differences in abilities in the middle of conversations, shopping, eating out, etc.?

5. You have a good chance of dealing with a disability someday as well.

According to the Social Security Administration, 3 in 10 workers will suffer at least a short-term disability in their lifetimes. In 2010, 5% of the adult population between 18-34 years old had ambulatory problems according to the US Census Bureau and those numbers rise sharply in seniors with 16% of ages 65-74 and 33% of ages 75+ having ambulatory problems. That was just over 19 million people who have trouble walking in 2010 alone.

John Rawls, in his seminal book, A Theory of Justice posited that a just society would be one that was designed without knowing one's own status within that society. Because we would be ignorant of our own status, we would want a society that honors all human beings regardless of status. The question of disability fits this well because able-bodied people become other-abled all the time. So making the world fit for the most people means that if your time comes, you don't have to worry about it. You will not lose freedom in addition to the other losses you suffer as a result of injury, illness or aging.

4. An inclusive world is better for business.

If you want the most talented people to work for you, you want to sell your product to the widest market possible, or you want to have the best products and services available to you, then you should support a world that includes the most people. By arbitrarily excluding people on the basis of anything other than their skills and talents, you risk having an inferior work force, inferior product or service or limited market. Inclusion is good business because the brightest and best are not systematically prevented from offering their talents and skills to the market. This, by the way, is true with any kind of inclusion, not just physical or mental ability. Deciding to exclude people because of their appearance, their membership in a group, their affiliations, their age or their disability is simply bad business because you will never know what brilliant ideas, visionary innovations, excellent skills or well-honed skills you've missed. Opportunity cost in commerce is important.

3. 10,000 people are turning 65 every day between now and 2030.

If you are a working person and pay taxes, you pay Medicare and Social Security taxes. These are entitlements that are supposed to ensure that you have your needs taken care of as you grow older. However, something called the "old age burden" affects this greatly. The old age burden is simply the number of people who are over the age of 65 compared to the number of people who are between the ages of 20 and 64 (working age). In 2010, that ratio was 22 older folks to 100 working folks. By 2030, that ratio will be 35 to 100.

Why is this important? Less accessibility means more people living in expensive long-term care that don't really need to do so. And that means high costs that are spread through the Medicare system, thus raising taxes and endangering the retirement years of younger folks. Universal Design means old folks will be able to live in their own homes, shop in the community, continue working and live higher quality lives. That, in turn means they will be less of a burden on the rest of us.

2. You want to live a long time.

As mentioned above, your chances of experiencing ambulatory difficulties increase with age. If you plan to grow old, you should support universal design because an inclusive world is an easier world to grow old in. One of the arguments for visitable housing is something called "aging in place." Not only should you want to reduce the burden of your elders on your work life while you are young, supporting Universal Design means that an accessible world will be waiting for you when it is your turn.

1. It's the right thing to do.

Yeah, we know this is an old school argument. But the fact is, as Dr. Robert Fuller has asserted in his The Nobody Manifesto, "We are all once and future nobodies." The central principle of Universal Design is the respect of the dignity of all persons. Supporting Universal Design is the right thing to do because respecting the dignity of individuals is the right thing to do. For some of us, doing and being right is important.

The concepts of social empathy and stigmatization are sometimes hard to grasp for many. When looking at the problems of physical barriers to movement for persons who need mobility assistive devices or who are fighting invisible, but real ambulatory challenges, we have something concrete (sometimes literally) to observe. But these barriers to our dignity exist in social space as well as physical space.

Our hope for User Friendly Vegas is that we can show that respecting the dignity of others, making room for as many people as possible, is a habit of mind and heart that is sorely needed in our society. And that the practice of Universal Design is important because it infuses into the system a way of thinking and acting that can benefit every one, especially any one who faces exclusion.

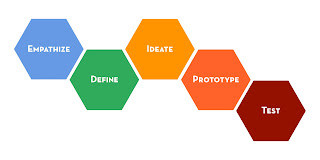

We chose the name "User Friendly" because it is a design term that implies empathy. All products and systems existed in the minds of a designer before they became a reality in space and time. Designers need to understand how users will use the design. This requires empathy. A designer has to put herself or himself into the place of the user and see how they will use the design in their everyday lives. Empathy is so important to design that it is the first step in Stanford’s Institute of Design’s iterative methodology model.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

We invite you to join us on this journey. You may choose not to do so and that is something we respect. But we hope that you will make that decision for reasons other than you think this topic is not "my issue" or not important enough to support.

Our message is simple: We want "To Make the World a Nice Place to Visit." That should be true everywhere for everyone.

If you want to join us, please help us with a small donation. The number of people contributing is just as important as funding the goal amount. We want to show widespread support for this so that we can get notice from a documentary funding source like PBS or Discovery or Sundance (or others).

If you want to join us, please help us with a small donation. The number of people contributing is just as important as funding the goal amount. We want to show widespread support for this so that we can get notice from a documentary funding source like PBS or Discovery or Sundance (or others).

No comments:

Post a Comment